|

A-T. Tymieniecka (ed.), Analecta Husserliana, Vol. XLVI, 147-154 Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1995

DANIEL J. HERMAN

TRANSLATOR’S INTRODUCTION

Tran Duc Thao was born September 16, 1917 in Thai Binh, in what would later become North Vietnam. He left for France in 1963 [sic - THD] where he pursued his philosophical studies. It was then and there that he met Sartre, Merleau-Ponty and Jean Cavailles who introduced him to the philosophy of Husserl. In 1941-42, under the direction of Cavailles, Thao did his doctoral dissertation on the Husserlian method, and under the strong influence of Merleau-Ponty deviated from common interpretations which made of Husserlian phenomenology a doctrine of eternal essences to a philosophy of temporality, of historical subjectivity and universal history. For, as Husserl used to say, “inner temporality is an omnitemporality, which is itself but a mode of temporality.”

It was then that lengthy dialogues took place between Sartre and Thao. These conversations were taken down in short hand with the aim of publishing them. Thao gave his own version of them when he stated that Sartre’s invitation was for the purpose of proving that existentialism could peacefully co-exist with Marxism on the doctrinal plane. Sartre minimized the role of Marxism in so far as he recognized its value solely in terms of politics and social history. The sphere of influence would be shared by both Marxism and existentialism, the former being competent with respect to social problems, the latter being valid solely as philosophy. Thao tried to point out to Sartre that quite to the contrary Marxist philosophy was to be taken seriously since it grappled with the fundamental problem of the relation of consciousness to matter. These dialogues with Sartre, along with the destruction of German fascism, necessitated a radical choice between existentialism or Marxism, Sartre and Merleau-Ponty having already opted for the former. Thao, owing to his phenomenological orientation, broke with existentialism with the publication of Phenomenology and Dialectical Marxism.1 Owing to this same orientation, the choice of Marxism created for Thao a need to rid the dual Hegelian and Husserlian phenomenologies2 of their idealistic form and metaphysical elements in order to salvage whatever else was left valid and place it at the service of dialectical materialism for a scientific solution of the problem of subjectivity.

Tran Duc Thao’s analysis of Husserlian phenomenology, especially the later writings, the Crisis and the “Origin of Geometry,” led him to a cavalier rejection of phenomenology altogether. The practical results of Husserl’s analyses are incompatible with the theoretical framework in which they originated. Meaning, which originates at the antepredicative level, cannot be the work of a transcendental ego that constitutes the meaning of the world outside of space and time, but is, rather, the work of a consciousness immersed in a historical becoming. Husserl’s transcendental ego turns out to be the actual consciousness of each man within his own actual experience. At this point, Thao points out, Husserl falls into a total relativism: “the merchant at the market has his own market truth.” Husserl’s constitutions of the world with the contemplation of eternal essences turns out to be a nihilism, wherein consists the crisis of Western man, which in turn gave birth to irrational man, the existential man whose claim is that the only sense of life is the lack of any sense, or Heidegger’s “being unto death.”

The solution to the crisis of Western man and others lie for Thao in dialectical materialism, thus the second part of the book: “The Dialectic of Real Movement.” What Thao stresses here is Husserl’s investigation turned right side up, by ridding it of idealistic formalism and thereby construction a new rationality, a stress on the concrete contents of experience. The relationship between consciousness and its intentional object is explicated by reference to the antepredicative level of conscious experience mediated by human labor. “The notion of production takes into full account the enigma of consciousness inasmuch as the object that is worked on takes its meaning for man as a human product.” The realizing of meaning is precisely nothing but the symbolic transposition of the material operations of production into a system of intentional operations in which the subject appropriates the object ideally, in reproducing it in his own consciousness. “This is true reason for man, who being in the world constitutes the world in the intensity of his lived experience.” And the truth of any constitution such as this is measured only by the actual power of the mode of production from which it takes its model. The humanization of nature through labor is how Thao accounts for how matter becomes life and consequently assumes human value.

Tran Duc Thao frankly admits that an interpretation of Marxism subject to the conditions of a personality cult engulfed Phenomenology and Dialectical Materialism in a hopeless metaphysical juxtaposition of phenomenological content to material content which paved the way for the return of an idealistic dualism.

Afterwards, Thao found, in his studies between 1960-1970, that in order to avoid the above-mentioned danger he had to minimize phenomenology, without, thereby overcoming the juxtaposition.3 These essays form his second major work, Recherches sur l’origine du langage et de la conscience.4

Tran Duc Thao’s analyses are divided into three parts: (1) the origins of consciousness by means of the indicative gesture, (2) the birth of language and making of tools, and (3) Marxism and psychoanalysis. We will briefly outline the first two investigations for they truly present Thao’s original contributions to the fields of anthropology, linguistics and, of course philosophy.

Thao’s investigations into the genesis of consciousness finds it to be due to the development of language which, in turn, is generated by human activity in the development of material conditions which precisely constitutes human labor as social labor.

The transition from animal psychism to human consciousness is effected by the prehominid. What distinguishes the prehominid from the animal is the indicative sign which constitutes the original form of consciousness. The indicative sign consists in pointing to a “relatively” distant object and thus establishing a relationship between the subject (pre-hominid) and an object that is external and independent. The reader will recognize here Thao’s version of the phenomenology’s thesis of the intentionality of consciousness, which states that consciousness is always consciousness of an object. Animals are incapable of pointing or indicating anything whatsoever as distant or external objects. At the prehominid stage, however, indicative gestures — pointing to the game to be chased — serve to coordinate group movements in hunting expeditions. As yet the indicative gesture remains a natural and unconscious gesture as it occurs only in an immediate biological situation. This unconscious gesture will become conscious when the members of the hunting expedition will not only indicate game to other members but to themselves individually, which means that the material gesture advances from a linear form (indicating the object to others) to a circular arc (signifying back to oneself as a member of the group). The reciprocity of the indicative gesture is thus essential not only for consciousness but more importantly for self-consciousness. Man’s objective material relationship with the environment entails a meaning experienced immediately, before it emerges on the conscious level as language. Thus, there is a language of real life which develops from the material conditions of social life. Language is not arbitrary, it is a constitutive moment of consciousness. Consciousness is language, prethematic or subconscious at first in so far as it is immersed in action, and thematic or fully conscious when the lived experience of material conditions is interrupted, providing thereby a pause, the pause that is precisely what occasions consciousness to take a look at or reflect upon that experience.

For Tran Duc Thao the origin of humanity, i.e., the moment when prehominid became hominid, coincides with the elaboration of the instrument into a tool. The most intelligent of the highest apes, such as chimpanzees, can only use their hands, and when they manipulate objects they do so only to satisfy their immediate biological needs. Here Thao makes an enormous vital distinction between the instrument and the tool.5 The instrument as a separate or external object to be manipulated by the organism is never viewed as separate or external. The animal works only under the compulsion of a situation of biological need, and thus can never abstract the moment of labor for the satisfaction of a need to introduce a mediating element between itself and the object of need. The object of biological need always occupies a central position in the animal’s perceptual field. Hence it cannot go beyond the stage of immediate and direct manipulation, since the total dynamic field does not allow for the introduction of a second object, in other words, does not allow for mediation, which is precisely what constitutes thinking. With man, however, the needed object is transformed through the mediation of the tool into an object of labor. Thus productive labor which marks the beginning of human activity, and the transition from nature to culture, became possible only when the prehominid had gone beyond simple pointing. At this stage he is already capable of an idealizing representation of the absent object to himself, but he can also create the ideal and typical form to be actualized in the tool.

The transition from the presentative indicative sign of the this here to the representative sign of the this absent is the first form of reflection and the manifestation of that “liberation of the brain” whereby man transcends the limitations of the present situation which always imprison the animal. After a certain dialectical development, however, it also permits man to escape reality and confine himself to symbolic construction by denying the reality of human life. Thus idealism is born from the transformation of these symbolic constructions into principles and therefore the negation of objective reality. Thus idealism, according to Thao, must once again be turned right side up.

When years later Tran Duc came to reflect upon this investigation, he confessed to having became stagnated on the pure formalism of the threefold combination of the “this” (here or absent) (T) in the motion (M) of the form (F). At the same time the development of these figures should have been able to account for the development of the various semiotic structures of languages as they originate in both humanity and a child. But a purely mechanistic combination done almost entirely within the horizon of dialectical materialism was expected to bridge the gap between the animal and man. Thus, Thao concluded that he had confused two entirely different semiotic formations — the gestures of the prehominid and language properly so-called, or verbal language which is specific to man — in a single confused representation of language.

In short, from the years 1960-70 to the early 80s, Thao was confusing the gestures of the prehominid with the language of early man, so that, on the semiotic plane, he was suppressing the essential difference between the most evolved animal and the most primitive man by reducing the specificity of human language to the development of a simple combination of emotional and gestural signs. This reduction, Thao admits, was due to a mechanistic metaphysics, a metaphysics which denies the dialectical unity of human history, depriving humanity, thereby, of its real meaning.6

Thao frankly admits that the third investigation, “Marxism and Psychoanalysis,” was written primarily as a concession to the times. The events of 1968 had profoundly influenced intellectual Communists, who naively thought that psychoanalysis was promising the world by shedding light upon the mystery of language. It didn’t take long for Thao to realize that psychoanalysis would be of no help with regard to the problem of sentence formation.

Mention has already been made that in his Investigation into the Origin of Language and Consciousness Tran Duc Thao had tried to correct Phenomenology and Dialectical Materialism by minimizing or even neglecting phenomenology in order to undertake an entirely materialistic approach to the genesis of consciousness, one rid of phenomenological subjectivism. This neglect, confesses Thao, was not so much a matter of choice as a response to the dictates of the political dogmatic deformation of Marxism engendered by the “proletarian cultural revolution.”

Today, Tran Duc Thao could rid himself of all philosophical taboos by developing a knowledge of man thereby restoring the dialectical unity of both theory and practice in a globalistic comprehension of world history.

Tran Duc Thao returned to France in September, 1991, taking up residence in Paris in order to renew his by now enthusiastic research with the aim of elaborating the project of the unification of science and philosophy starting with the origins of consciousness and its development with the historicity of the world. Enriched now by the contributions of Husserlian studies of the third period, Thao began to write feverishly, intuiting correctly that he had little time left in which to author what would be his third and last book. It was not to be completed, for Tran Duc Thao died tragically as a result of an accidental fall on April 24, 1993. He was 76.

Tran Duc Thao and I became very active correspondents for about a year, before his sudden death. I was translating his articles as soon as he would submit them to me, with the hope that his forthcoming book would somehow alleviate his dire financial situation as well as leave to posterity his final philosophical testament. This testament now consists of three essays with two appendices. One of those essays and the two appendices follow.

The first essay7 sets up a dialectical logic in stark opposition to formal logic, which, at first impression, would lead one to think that the former logic is very much in opposition to the customary way of thinking. Formal logic with the “three laws of thought” constituting its backbone considers the present instant to be immobile, so that movement would constitute a passage from one immobile instant to the next, with the net result that formal logic could not possibly be faithful to reality as movement would turn out to be a succession of instants. Such a metaphysical conception of things which thinks in terms of strong dysfunctions; either/or — yes, yes/no, no, is a thought which thinks outside of time, outside of the temporal flow. Against this false metaphysics according to which something either exists or not, Heraclitus avers, to the contrary, “everything is and at the same time is not, for it flows.”

This formal logic with its succession of instants was also refuted by Hegel when he rejected the excluded middle term. Formal logic says that something is either A or ~A; there is no middle term. To which Hegel replies, there is a third term in that very same thesis. A is itself that third term, for A can be either A+ and ~A. Thus A is that third term that one wants to exclude.

The formula of Heraclitus, taken up by Hegel, “Everything is and equally is not,” was abbreviated in such a way as to give rise to regrettable confusions, for one was led to think that for dialectical logic being itself is not, which is contrary to common sense. Thus both logics, opposed to each other as they were, had to be synthesized. since both did justice to reality and common sense.

This task, according to Thao, was left to Husserl, and was accomplished by means of the temporalization in the Living Present.8 This task Husserl has left for posterity to implement. It yields a dialectical globalistic interpretation of human history.

Real time, according to Husserl, is not clock time as Aristotle conceived of it in his famous definition, “time is the measure of motion, according to a before and an after,” a definition which until Husserl had never been challenged.9 Aristotle’s conception of time makes of the instant, an immobile instant, and motion is once again made incomprehensible, for how can it be reconstructed given its immobility?! For Husserl, on the other hand, “The Present which flows (i.e., the Living Present) is the Present of the movement of flowing, of having flowed, and of having yet to flow. The now, the continuity of the past, and the living horizon of the future outlined in protention, occur consciously ‘at the same time,’ an ‘at the same time’ which flows.” With phenomenological time, time is no longer considered as a fourth dimension of space, says Thao, and we are now able to effectively reconstruct history as the measuring of humanity with its wealth of real relations instead of as the abstraction of reciprocal causal relations.

Thus, Tran Duc Thao applies the theory of the Living Present as a theory which alone can account for individuality in the sciences, especially the science of biology.10

Thao, once again, finds Aristotle to be at fault when he maintained that, “science concerns only the general, existence concerns only the singular.” For three thousand years this Aristotelian motto went unchallenged, as a science of singular existence was never really considered, even though in its practical application science had to deal with that existence. Those very dealings only amounted to meeting points. Science would never grasp existence in itself or the singular individual as such, the individuality of that existence being reduced as it was to an abstract point. The Living Present, continues Thao, is first of all and essentially the concrete individuality of singular existence constituting itself, at each instant, in the temporalization, or intrinsic movement of that very instant, its interval of becoming the completion of which is accomplished by itself in its passage to the following instant.

The evidence of the internal dialectic of the Living Present can be found in the analysis of biological temporalization. We won’t extend ourselves on this analysis. Suffice it to say, in Thao’s own words, that “At each instant biological individuality surges as a system of functions inherited from the past, that which has been sedimented in its past and yet remains actually present in Retention which blends with the actual Now, which provoked tension in the metabolism of the functioning of these functions, or in Protention into the imminent future.”

His conception is an innovation of Husserlian temporality.*

The University of West Florida

NOTES

1 Tran Duc Thao, Phénoménologie et Matérialisme Dialectique (Paris: Minh Tan, 1951); Phenomenology and Dialectical Materialism (New York: Gordon and Breach, 1971) trans. and introd. Daniel J. Herman and Donald V. Morano (Dordrecht, Boston, Lancaster, Tokyo: Reidel Pub. Co., 1986) 2 See Appendix A. 3 “Un Itinéraire” published in the French journal Révolution (June 7, 1991, no 588). 4 Tran Duc Thao, Recherches sur l’origine du language et de la conscience (Paris: Editions Sociale, 1973; Investigations into the Origin of Language and Consciousness, trans. Daniel J. Herman and R. L. Armstrong (Dordrecht, Boston, Lancaster, Tokyo: Reidel Publishing Co., 1984). 5 A distinction which is totally ignored by Jane Goodall, who use these terms synonymously. No wonder! Had she been properly educated in her field she would have benefitted not only from Thao’s anthropological research but from Koehler’s as well. Koehler years ago had already pointed out in his classical experiments with apes that they cannot represent to themselves an absent object, hence they are incapable of thinking, if thinking at its minimum consists in taking a distance from what one thinks. 6 Tran Duc Thao, “Un Itinéraire,” op. cit. 7 Tran Duc Thao, “Pour une Logique Formelle et Dialectique.” 8 Tran Duc Thao, “La dialectique logique comme dynamique de la temporalization.” 9 Thao forgets Bergson whose distinction between clock time and real duration undoubtedly influenced Husserl. 10 Tran Duc Thao, “La théorie du Present Vivent comme théorie de l’individualité.”

* I wish to express my heartfelt gratitude to Arlene Jewell who sacrificed most of her holiday time to type these manuscripts.

A-T. Tymieniecka (ed.), Analecta Husserliana Vol. XVLI, 155-166 TRAN DUC THAO

DIALECTICAL LOGIC AS THE

GENERAL LOGIC

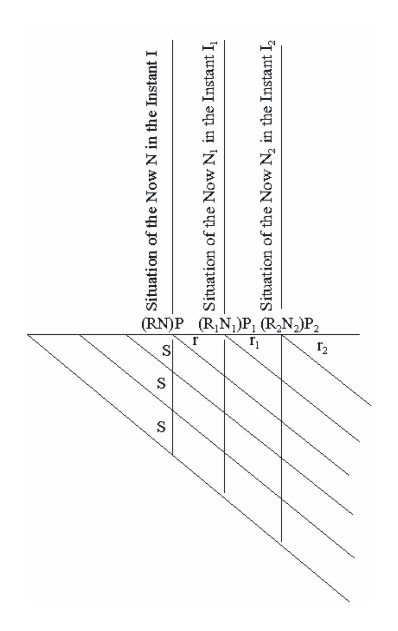

Aristotle defined time as the measure of motion according to a before and an after, from which it follows that the instant wherein that measure is determined by the hand of a clock, presents itself as a limit which separates the past from the future, and at the same time possibly connects them by simple contiguity, in such a way that that instant remains immobile in its punctual instantaneity. This immobility of the instant as such, renders the motion of things incomprehensible, seeing that this motion should necessarily coincide with an infinity of purely static positions. It is clear that the point in time is but an abstraction, albeit a necessary one for measurement. But to define the instant as a point is to reify an abstraction which amounts to a suppression of the future itself. It was only in the first part of the twentieth century, that, with the development of the phenomenological method, Husserl was able, in the third phase of his creative activity, to grapple with the problem of temporalization in the living present and, thereby, transcend the Aristotelian difficulties by bringing to light the dialectic of the instant in the instant itself. It is true that Husserl’s thought on the Living Present was limited to the domain of the pure subjectivity of lived experience. We can, however, take up its essential content again, giving it necessary development and transformation in order to elaborate a dialectical logic as a general dynamic of temporalization, in other words, a general logic of being in its motion and objective and subjective becoming. Such a logic would open the way to the task Husserl left to posterity in the Krisis, the elaboration of a really universal conception of the exact, historical, social and human sciences, which in turn would lead to an effectively rational comprehension of the problem of man and his values in its dialectical complexity, a globalistic conception of the history of mankind. We can now give a more precise description of the living present by considering the situation of the actual Now, and by bringing to light the internal retention of the present instant in the flow of the Now to protention. This gives us a diagram of temporalization:

The flow of time constantly contains in depth, a sedimentation from high to low which functions as retention from low to high. Retention R, resulting from the sediments S in the instant I, finds itself connected with the situation of the Now N in that instant I. The being still present in retention R contracts, by virtue of its connections with that situation of N, a tension upon the imminence of future,or protention. We place in a common parenthesis retention R and the now N: (RN) in order to indicate that the content of R inherited from the past, as that which is still present, immediately flows in the now N with which it blends, because it is precisely still present now. And it is this Now N, bearing within itself the retention R of its past still present now, which flows and comes to the flowing upon the imminence of the future in the protention P. “The Present which flows, is the Present of the movement of flowing, of having flowed, and of having yet to flow. The now, the continuity of the past and the living horizon of the future, which is outlined in protention, are conscious ‘at the same time’ and this is an ‘at the same time; which flows.” (Husserl, Unpublished ms. C2 I 1932—1933 — quoted by Tran Duc Thao, Phénoménologie et Matérialisme Dialectique, p. 143. English translation, p. 230.) One should notice that the situation of the Now N, here symbolically indicated by a vertical line above N, contains in reality the wholestate of the world.And it is in the concomitant connection with the state of the world that the retentional heritage of the past blending with the actual present Now assumes a tension upon the imminence of the future as protention. The classical theory of time only took into account the linearity of the simple phenomenon of the flowing which led thereby from the measure of a clock to the mathematical definition of time as the number of motion according to the anterior and the posterior. As a result the present instant as simple limit between the past and the future was abstractly reduced to a static point. Movement and becoming were thus made incomprehensible, and there was even less a question of historical reality and of effective historical sense. Time was reduced to a fourth dimension of space, a dimension which, suppressing the richness of real relations, came to the abstraction of causality, with its various modes of reciprocal action as causal complexes It is only with the consideration of the Living Present understood in its effective reality as substance which posits itself as subject that time appears to constitute itself in that primordial Present in three directions in constant dialectical connection: direction in length, of the flowing as such; direction in depth, of the retentional sedimentation; and the concomitant direction of all the connections with the state of the world. And it is to be noticed that this state of the world comprises within itself a plurality of stages historically in formation and in systemic superposition. The Husserlian discovery of the living Present with its threefold temporalizing direction thus paves the way for the task of a radical remodeling of the way of thinking with the constitution of a new logic as the Logic of Temporalization in the Living Present — or the Logic of the Living Present. This new logic opens the perspectives for a concrete solution, both theoretical and practical, of the fundamental problems of the philosophical tradition: the general, the particular and the singular, necessity and contingency, mediation, negation, self-negation and the negation of the negation, contradiction, essence and existence, quality and quantity, being in itself, being for others, being for itself, greatness, and smallness, servitude and freedom. Between the already acquired givens of retention as the heritage of the past and protentional tension over the imminence of the future, there is, of course, a fundamental opposition which defines the internal contradiction of reality present in the instant, a contradiction which constantly implies its unity, and the strife of its contraries. The unity of the contradiction between retention and protention posits the reality of the present instant in the identity of its being according to its immediate logical form: (I) that which is, is. At the same time, the strife of contraries, the strife of the protentional imminence of the future with the retentional past, brings it about that this same present reality sinks in the movement of its disappearance as it is expressed in the mediated dialectical logical form: (1) That which is, is; and at the same time, it is and is not, in the sense that it is no longer. This disappearance of the Now in the past is expressed in the immediate negative form of the logic of temporalization: (2) that which is not, is not. However, the past in the movement of its disappearance still maintains itself in its retentional sedimentation, which expresses itself in its mediated dialectical logical form: (2) that which is not, is not; and at the same time, in the form of that which is no longer, it still is. Such a sedimented retention completes the intrinsic movement of the present instant, which posits the reality of that instant in the completed being, as it is expressed in its total immediate logical form: (3) that which is, is either A or —A; there is no middle term. At the same time, this completion of the intrinsic movement of the present instant I brings about, by that very same sedimented retention, the passage to the following instant I, which is expressed in its total mediated dialectical form: (3) that which is, is either A or —A; and at the same time, in the form of being already in the appearance of the future, it is itself and another. Itself and another, that is, in the intrinsic movement of the instant I itself, the passage to the instant II. In other words, in the intrinsic movement of the present instant a double passage is brought about; the instant is the instant of the passage of the past still present to the imminence of the future, of retention to protention. And that passage terminates as the passage of the actual instant to the following instant. Actually, the sedimentation of Instant I in its own movement of “flowing, of having flowed, and of having yet to flow” produces an internal retention R of itself in the flowing of its Now N and under its protention P, in such a way that this internal retention appears as the imminent future in and under protention P. And this imminence of the future as the appearance of the imminent future precisely constitutes the completion of the actual Instant I, a completion which effects its passage to the following Instant I1. At Instant II the internal retention R of the preceding instant frees itself by finding itself connected with the new situation, the situation of Now NI in that Instant I1. The passage of each present instant I to the following present I1 is thus effected in the intrinsic movement of the instant I itself, as the completion of its movement of “flowing, of having flowed, and of having yet flow” so that this effected passage is itself a flowing from one instant to the other. The intrinsic movement of each instant thus presents itself as a lapse of time. And the continuation of the flowing of instants lapsing into one another is the definition of the flow of time.

APPENDIX A THE DUAL HEGELIAN AND HUSSERLIAN PHENOMENOLOGIES “Time,” says Hegel, “is the notion itself in the form of existence.”1 At the very heart of Hegel’s rational dialectic we find the dialectic of time as notion in the form of existence. It is only with Husserl, however, with his theory of the living present (Lebendige Gegenwart) mentioned in Group C of his unpublished works,2 that, we get for the first time a precise description of the consciousness of time, particularly in the Preface to the Phenomenology of Spirit. The Living Present is the movement of primordial consciousness, it is the temporalizing temporality always present to itself in a preservation and perpetual conquest of self: the past is retained therein as that which still is (retention) and the future is announced therein as that which already is (protention). This is a continual movement in which each present moment immediately passes into retention and sinks more into the past, but into a past which still is; meanwhile the future here and now possessed in protention is actualized in a lived present; in this continual movement the self remains identical to itself, while renewing itself constantly; it remains precisely the same only by always becoming another, in that absolute flux of an “eternal Present.” “The Present which flows is the Present of the movement of flowing, of having flowed and having yet to flow [die Gegenwart des Verströmens, des Absträmens und des ZustrOmens]. The now, the continuity of the past, and the living horizon of the future which is outlined in protention are conscious ‘at the same time’ and this ‘at the same time’ is in ‘at the same time’ which flows.”3 In the Preface to the Phenomenology of Spirit Hegel writes: “. . . everything depends on grasping and expressing the ultimate truth not as Substance but as Subject as well. The living substance, further, is that being which is truly subject, or what is the same thing, is truly realized and actual solely in the process of positing itself or in mediating with its own self its transitions from one state to its opposite.”4 In Husserlian language we can translate “substance that is truly subject” as the Living Present which constitutes itself in the movement of its retentional past, its actual present and its protential future. “Being which is truly subject . . . or, what comes to the same thing, the process of positing itself, or mediating with its own self in and from its other,” this is the Living Present which always remains identical to itself as such in its flowing, at the same time that it always becomes another by positing itself in the movement of its retentions. It is thus truly “the mediation with its own self in and from its other.” We present below in two face to face columns passages which are characteristic of Hegel’s Preface to the Phenomenology of Spirit and their equivalent in the Husserlian phenomenology of the Living Present

1

G. W. F. Hegel, Preface a La Phénoménologie de l’Esprit,

edition bilingue de Jean Hyppolite (Paris: Aubier, 1966), pp.

46—49 (The Phenomenology of Mind, trans. J. B. Baillie

(New York: Harper Torch Books, 1967), p. 104

APPENDIX B THE DIALECTIC OF ANCIENT SOCIETY

INTRODUCTION The birth of a historic formation is mediated by the dialectical negation of the preceding formation, a negation which implies the triple meaning of a suppression, preservation, and sublation.* Thus, the birth of the first social formation with Homo habilis contains the negation of the animal grouping that had arrived at its highest evolutionary level with the Australopitheci, which implies the suppression of the animal mode of life founded on the direct exploitation of environmental resources. The instruments or elementary tools prepared or elaborated by the most intelligent apes still belong to the animal level; they are only prefigurations of the production of the means of existence, such as we first see them in Homo habilis; i.e., a complex and well-defined system of tools enabling the construction of rudimentary huts with the whole forming an encampment. In short, the negation of animality with its passage to humanity appears first of all as a suppression of the essence of the animal grouping (to wit, immediate life as a whole’s depending upon the surroundings) by the first system of production with the social relations expressed by the first language of social cooperation in the first local community of Homo habilis. At the same time, this same negation has the meaning of a preservation of the use of brutal force in the relations between the local communes, different and opposed as they are in their quarrels about hunting and gathering grounds.

Finally, this preservation of violent relations is accompanied by a sublation of that violence by the language of hostility, which sanctions the relation of force by a symbol of strife, a symbol, which to a certain degree tends to replace the real struggle.

The "No!" energetically proffered by the infant of eighteen months expresses an interdiction which sublates the use of real violence by the tone of symbolic violence, socially comprehensible, which progressively diminishes the spasmic violence of the original behavior of opposition.

In short, the passage from the last animal grouping to the first human society is mediated by a negation which is at the same time suppression, preservation and sublation.

The case is the same for the passage from the last primitive society to the first civilized society.

* * * Thus, according to the investigations of historical archeologists, notably Jean Louis Huot and his colleagues, the ancient social forrnation appeared in the Orient during the age of copper, at the beginning of the third millennium before our era, in the essential form of the City System comprising the town with its rural suburbs. Beyond these suburbs, tributary agricultural communes were to be found. Still further away were independent Neolithic agricultural communes which were subject to being pillaged by the city.

The birth of the ancient social formation thus presents itself as a first negation of the tribal social formation, as the suppression of that formation in the territory of the city system. This suppression implies, at the same time, the preservation of that same tribal structure beyond the city system within the agricultural communes. And that preservation contains the sublation of that same tribal formation by the imposition of tribute and service upon the nearest agricultural communes, and occasionally by looting expeditions against more remote agricultural communes.

In this way, this first negation gives birth to the city system comprising the town and its rural suburbs, which dominate tributary agricultural communes. These as a whole appear to be dominated.

The city, therefore, constitutes a system of domination in ancient society or social formation. The fundamental quality or essence of that social formation is evidently defined first of all by its system of domination, and not by its dominated elements.

If we consider the city‑system of town and rural suburbs, it is important to notice that these suburbs imply a division between individual lands and communal lands of the city.

The individual plots of land are appropriated by peasant families and by the diverse personalities of the religious, military, and merchant aristocracy. The form of that appropriation moves from possession or individual property, more or less recognized by custom or law, to private property, properly so‑called. which appears with the first use of iron in the Greco‑Roman, Achaemenian and Chinese cities (in Latin: arva).

On the other hand, there always remains in the rural suburbs of towns a reserve of communal lands (in Latin: ager publicus). These communal lands belong to the city and have nothing to do with the tributary agricultural communes.

In the city, the work of production is secured by the free men and their dependents (slaves, serfs, and other servants). As a result of this, there ensues a division of social relations comprising, on the one hand, the small family initiatives in production, with a small number of dependents and trade in local markets using the simple form of value, and, on the other, the larger initiatives in production directed by aristocratic merchants, with a great number of dependents and trade in more or less distant markets, which. with the use of copper or primitive bronze, saw the use of the developed or complete form of value.

The social system of the city, thus, appears, from its Sumerian origins, to be essentially a system of exchange and dependency, developing within a complex unity of contraries, comprising the free opposition between traders, the imposed opposition between aristocrats and common people, and the enforced opposition between master and servants. A unity of contraries such as this is secured and symbolized by the ancient state. Given the particular conditions in Asia, a continental mass that has a very restricted number of streams and coastal areas, areas suitable for market places were less numerous, as a whole, than in Europe. Consequently, in spite of the development of the cities, the proportion of agricultural communes remained high there. which secured the power of the aristocracy, whose armed intervention was necessary for the exacting of tribute. Under these conditions the form of government could only be monarchical.

It was only in the particular condition of the carved up geography of Greece and Italy, at a moment when a powerful commercial current imposed itself between the old civilizations of the Orient and the still Neolithic countries beyond the Alps, that it was possible for cities to develop during the age of iron and to then extend over the greatest part of the territory previously occupied by agricultural communes. Only there could ancient monetary relations bring about a considerable development of slavery, which then gave simple citizens sufficient leisure to enable them to participate in the power of the state in the form of a democratic regime alternating between two parties: the aristocratic and the popular.

The form of the ancient state, however, whether democratic or monarchical, does not change its essence, which is to guarantee within the city, or federation of cities, regularity in trade and the domination of free men over the servants; this is the essential function of the state. The exacting of tribute from surrounding agricultural communes is a regular but nonessential function, since the system of production within the city, can, strictly speaking, given the economic unity of the town with its rural suburbs, be self‑sufficient without tribute.

The higher number of tributary agricultural communes of cities in the Orient promoted the predominance of an aristocracy which was in charge of exacting tribute, thus leading to the monarchical form of government, The Greco‑Roman states also had tributary agricultural communes, but they were few in number, so that the exaction of tribute could not swing the balance decisively to the side of the aristocracy to the point that, as in the Orient, this would mandate a monarchical form of government. However, the very superiority of ancient democracy brought about such a development of slavery and a colonialism, which for all practical purposes was enslaving, that the Roman Empire ended with a return to an increasingly monarchical regime.

In short, the opposition between monarchy and ancient democracy was only formal. The differing number of tributary agricultural communes entailed important, but nonessential, difference. The ancient society owed its essential unity to the domination of the city system over the agricultural commune.

NOTE

* The author uses surpasser which literally means "to overtake"or "to go beyond," to denote "synthesis" in the Hegelian dialectic. Hegel used "aufheben" which means to "raise" or "elevate" but since in his phenomenology "aufheben" means not only to raise but to raise on a higher level, insofar as the synthesis has preserved within itself both of the previous movements of the dialectic, this unique movement in the dialectical process therefore must be denotated by a unique term, and to that purpose we have chosen the term suhlatinn adopted by J. Baillie in his English translation of Hegel's Phenomenology. (Translator's Note)

THD đưa lên mạng ngày 22-11-04

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||